Jeff Bennett, Design Manager

Bryon Maxey, Engagement Manager

Since the early years of Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs), Academic Innovation project teams have explored and experimented with ways to expand and cultivate a global learning community. Our efforts toward multilingual translations of our MOOCs have played an important role in further opening up this global community. From early experiments translating the University of Michigan’s first MOOC — “Model Thinking” from Scott E. Page, PhD, John Seely Brown Distinguished University Professor of Complexity, Social Science, and Management — to Mandarin, to collaborative partner efforts translating U-M MOOC video subtitles into several languages via Coursera’s Global Translator Community, along with slightly more ambitious Course translation efforts in the “Successful Negotiation” MOOC from George Seidel, JD, Professor Emeritus of Business Law, into Spanish and Portuguese, we have facilitated greater access to U-M’s open learning experiences through translation.

In this post, we briefly examine two case studies representing some of our more recent MOOC translation efforts. Both cases are drawn from translation efforts of the “Programming for Everybody (Getting Started with Python)” MOOC from Charles Severance, PhD, Clinical Professor of Information (better known as Dr. Chuck) into Arabic on Coursera, and Spanish on edX. Through our work, and by examining these case studies, we aim to consciously build upon Academic Innovation’s early commitment to cultivating global community and increasing access through translation, while also acknowledging MOOC translation as a very new field of exploration and experimentation in the still-nascent learning environments MOOCs represent.

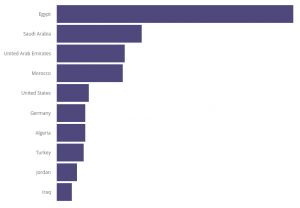

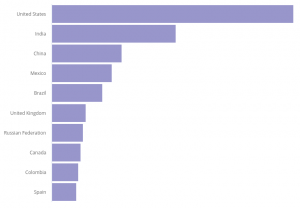

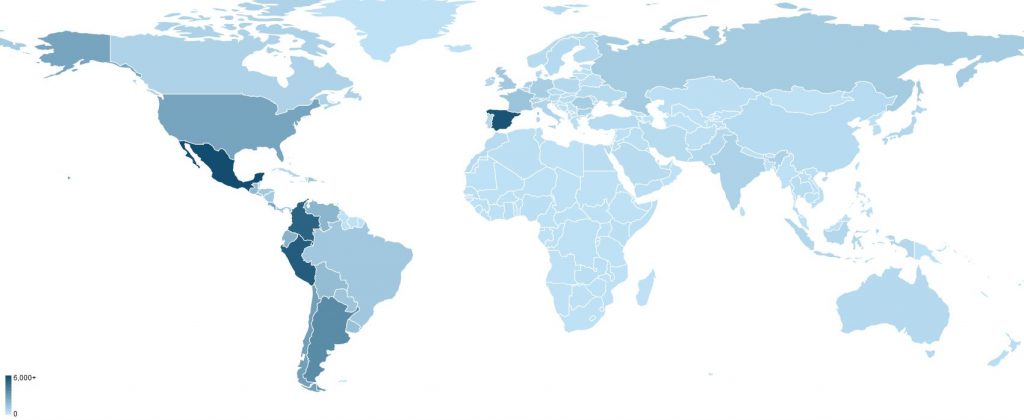

The initial translation of “Programming for Everybody” into Arabic was in collaboration with our learning platform partner, Coursera, through the Coursera for Government initiative. The translation effort was targeted to a specific audience of largely bilingual Arabic-English government employees in the Gulf region for whom increased access to our MOOC content in Arabic was a priority. While successful as a scoped translation effort, we also learned — as in any collaborative effort — that developing and setting shared standards of scope, scale, and logistics for a translation is important at the outset of a project. A particularly welcome surprise in this process of translation was the organically-generated reach and resonance of “Programming for Everybody” in Arabic far beyond the initial target audience in the Gulf region, with much greater learner representation in Egypt and significant learner representation in Morocco as well. A similarly welcome outcome of this translation effort was the reach into almost entirely new audiences compared to typical learner locales on major MOOC platforms like Coursera and edX [see figures below].

On edX, Dr. Chuck worked closely with us throughout the Spanish translation process. The current version of the Spanish course contains captioned videos, quizzes, programming assignments, and readings, all in Spanish. Chuck also translated the course textbook into Spanish, which is also available as a separate open resource. So far, the course has reached more than 30,000 learners from 102 different countries including Mexico, Spain, Peru, Columbia, Argentina, Chile, Costa Rica, and Ecuador.

It’s not an easy process to translate a course. Thinking through the work we’ve done, we want to share some important things to think about when embarking on a new translation project. First, when deciding which courses and content can be translated, keep in mind that you’ll need to think about your team’s resources and bandwidth. Translation files need to be located. Vendors for translation need to be approved, utilized, and reviewed appropriately. Video and programming assignments may require special skills to be edited effectively.

It is extremely helpful to have someone on the translation project team who has at least an intermediate level of fluency in the target language, as vendor translation files should be reviewed, and having some language knowledge is essential to ensuring course items are placed in the correct location.

We also recommend reaching out to faculty early in the process, especially if any special programming code or additional tools need to be translated in order for learners to feel successful.

Through this process, we’ve learned translation “…has gone through many turns…[o]ne central feature of this evolution is the ‘explosion’ of the boundaries of text (written and/or spoken) and the related ongoing development of new text forms and (their) translation modes (66).”1 Consequently, defining translation is complex in light of recent developments. Nevertheless, we’ve determined that there is value in a working definition of translation in order to continuously improve our initial experiments in MOOC translation. This has led us to consider a spectrum of viable translations, which we continue to explore. What are similar or parallel experiences you have had in your own course translation endeavors? What has worked and what has not worked? What should we all think about when beginning a translation project, both practical considerations, and broad strategy for quality translation? We’re looking forward to further exploration of these questions.

1 Gambier, Yves, and Ramos Pinto, Sara, eds. Audiovisual Translation : Theoretical and Methodological Challenges. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2018. Accessed September 13, 2019. ProQuest Ebook Central.

“From Translation Studies and audiovisual translation to media accessibility: Some research trends”

Aline Remael, Nina Reviers and Reinhild Vandekerckhove University of Antwerp