Jeremy Nelson, Director of the XR Initiative

In this week’s MiXR Studios podcast, we explore nuclear engineering and how we will recreate the decommissioned Ford Nuclear Reactor in virtual reality. We talk with Brendan Kochunas, an assistant professor of Nuclear Engineering and Radiological Sciences at the University of Michigan to learn more about his interest in resurrecting this 1950s reactor built to honor the casualties of World War II and study peaceful uses of nuclear power. Brendan has been exploring VR as a technology that can be used to recreate what it is like to operate a reactor and provide agency to enhance learning goals for nuclear engineering students.

In this week’s MiXR Studios podcast, we explore nuclear engineering and how we will recreate the decommissioned Ford Nuclear Reactor in virtual reality. We talk with Brendan Kochunas, an assistant professor of Nuclear Engineering and Radiological Sciences at the University of Michigan to learn more about his interest in resurrecting this 1950s reactor built to honor the casualties of World War II and study peaceful uses of nuclear power. Brendan has been exploring VR as a technology that can be used to recreate what it is like to operate a reactor and provide agency to enhance learning goals for nuclear engineering students.

Brendan talks about his work with The Consortium for Advanced Simulation of Light Water Reactors (CASL) and virtual reactor simulations over the last couple of decades. In 2003, the Ford Nuclear Reactor was decommissioned, which forced U-M students to visit other reactors for hands-on learning. Otherwise, students were forced to explore nuclear engineering in areas other than reactors. There are a number of current staff and faculty in the department that worked directly with the Ford Nuclear Reactor that Brendan will consult with on how best to recreate the environment in VR. He also shares an interesting story about how the reactor was used to help Ford redesign their automatic transmission.

The XR Initiative has funded the creation of an XR Nuclear Reactor with Brendan and his team. We have begun working with him and his undergraduate and graduate students to create 3D models of the Ford Nuclear Reactor. We will build a fully functional VR reactor that students can experience what it will be like to be in the reactor and they will be able to run experiments and simulations to create an exceptional learning experience.

I had a great time talking with Brendan about his work and am excited about the future of XR in the nuclear engineering program at Michigan. Please share with us what you would like to learn more about in the XR space at [email protected].

Subscribe on Apple Podcast |Spotify

More about Brendan Kochunas

Dr. Kochunas’ research focus is on the next generation of numerical methods and parallel algorithms for high fidelity computational reactor physics. His areas of expertise include neutron transport, nuclide transmutation, multi-physics, parallel programming, and HPC architectures.

During his time as a PhD student he initiated development of the MPACT code that has since become the main deterministic neutronics tool within the CASL (Consortium for Advanced Simulation of Light Water Reactors) project. MPACT was not only born out of his PhD research, but has also become a central research tool in the work of more than 10 other PhD students in the NERS department.

Transcript: MiXR Studios: Episode 4

Jeremy Nelson (00:09):

Hello. My name is Jeremy Nelson. Today we are talking with Brendan Kochunas who is an assistant professor of nuclear engineering and radiological sciences at the University of Michigan College of Engineering. And we are going to be talking about building a virtual nuclear reactor and how XR can enhance the education of Michigan students. Coming up next in our mixer podcast.

Jeremy Nelson (00:39):

Welcome, Brendan. Thank you for taking the time to join us today.

Brendan Kochunas (00:43):

Oh yeah, no problem. Thanks for having me.

Jeremy Nelson (00:46):

Yeah, no, we’re really excited to have you join the mixer podcast. I’m really excited to be working with you on your nuclear reactor project. Love to learn a little bit more about you and your background and what brought you to this space and wanting to do this.

Brendan Kochunas (01:02):

Yeah. Um, so, you know, I, I think I’ve had kind of a little bit of exposure to, to these kinds of technologies in the past, but not too much exposure to sort of the ways in greatest, um, extended reality, uh, things, things that are out there and, and certainly not in any capacity for teaching, you know, in terms of the recent capabilities, uh, actually the, the one you showed me for the international space station is kind of the, the, the thing that really, uh, for me allowed me to, I think better grasp, you know, what’s possible today, uh, and how people can interact with these spaces. And it’s, it’s, I mean, all of that to me is really exciting. Um, but you know, this concept of virtual reactor has been around, um, for a while. So I’m coming into this having worked on a very large department of energy project that went for about 10 years or just wrapping up, this is our last, uh, last year, just a couple of months left.

Brendan Kochunas (02:11):

It was called, uh, it was called CASTLE. It stood for, um, consortium for advanced simulation of whitewater reactors. And, uh, you know, the mission of that project was really to advance the modeling and simulation capability of nuclear reactors. And early on, you know, in the first year of this project, they invested quite a bit into VR experiences. And so, you know, we have this old figure from our, our picture, I guess, photograph from our project with the then secretary of energy, Steven Chu, you know, with the goofy goggles on inside one of those, uh, 3D caves. You know, that was 10 years ago, things have come a really long way. Um, but that’s, that’s kind of planted the seed I guess.

Jeremy Nelson (03:02):

So, you know, you’re well aware, I wasn’t completely aware, but there is a, there had been a nuclear reactor on our campus here at University of Michigan. And could you talk a little bit more about that and like the significance of that and, and why that played into your interest in building it virtually?

Brendan Kochunas (03:21):

Yeah, definitely. That’s one of the things I think is most exciting about this project. Um, so I think it was, you know, back in the 1950s the University of Michigan really endeavored for its first large campus wide kind of fundraising event. And it was to establish this Michigan Memorial Phoenix project. And so this Memorial was for the members of the University of Michigan community. You sacrifice their lives in world war two. You know, there’s a, in the university record, I think a very moving speech by then president, Ruthven of the University of Michigan. I’d like to read just a maybe short excerpt from that to give you a sense of, I think the ambition that the founders of this project had. You know, which is, you know, to me inspiring but yeah, you know, there, there’s, uh, he gave an address on Memorial day 1948 when they were just, I think kicking this effort off, you know, and president Rufven asks rhetorically in his speech, you know, can there be a fitting Memorial for those, the heroes of the war that produced the atom bomb.

Brendan Kochunas (04:46):

And there was only one appropriate kind of war Memorial a Memorial that will eliminate future war memorials. Uh, and so that’s, that’s the level of ambition that they were, they were kind of reaching for. And, and you know, they kind of kick the project off, the statement is, you know, here like the Phoenix bird of ancient legend, Adam’s force will rise from the ashes of its own destruction, to point the way to a better, fuller, happier life than man has ever known. The monument proposed by Michigan transcends the conventional living Memorial. It will be a dynamic, working, life serving memorial that provides a rare opportunity to answer the challenge of art here or dead. To you from failing hands, we throw the torch, be yours to hold it high.

Jeremy Nelson (05:31):

I like that.

Brendan Kochunas (05:33):

Yeah. I think being able to have this project contribute sort of to the, the history of this, um, is, you know, uh, a unique opportunity. And as I’m coming into this project and you know, the, the vision I have for it, you know, that’s sort of sitting there, um, in the back of my mind, you know, trying to be kind of like the guiding principle for what can achieved and what can we do, um, in this work. And yeah so, you know, the project established the first research reactor at a, you know, at a university in the United States. It got a lot of funding from the Ford motor company, so it was the Ford nuclear reactor. It was also one the reactor that, uh, that was funded solely from sort of non-government sources. So in that sense, they weren’t necessarily beholden to, um, research missions directed by the federal government.

Brendan Kochunas (06:32):

They had a little more freedom to pursue types of research that they were interested in. Yeah. But, uh, you know, unfortunately the reactor was decommissioned, deconstructed, permanently shut down around 2003. And for our department, you know, that’s, it’s a really kind of Keystone piece of infrastructure for, for research and teaching. And it’s difficult to replace something like that. And you know, I, I think right now with extended reality technology, you know, we’re able to make a really good go at providing that resource again. So I like to think of it as, as the Phoenix is rising again, but at this time virtually.

Jeremy Nelson (07:13):

Right, right. Well, yeah. What I’d love to hear a little bit more about how students used to interact with the react or how that was built into the curriculum or helped with their education as becoming a nuclear engineer. And then how do you see that with this new virtual reactor that we’ll be building with your team, how do you see that applying for future generations of engineers?

Brendan Kochunas (07:35):

Yeah, so there was, you know, one in our department one course, a senior level course dedicated to this reactor laboratory course and for universities with nuclear engineering programs that do have a research reactor, this is kind of the standard part of their curriculum. And you know, you’ll basically do experiments in there to sort of give you some notion of how the reactor operates, you know, how do you turn it on safely? How do you turn it off? What types of things can you measure from it? How do you do those measurements? A lot of stuff like that. So, you know, the course was offered typically in the winter semester and I think there were about eight or so experiments that the students did throughout. And, you know, this was a course that was taught, I think actually maybe before the department itself was established. So the reactor helped the university and the college of engineering establish the department in the late fifties. Yeah. So, you know, pretty much from, from when it came online and construction was completed in the, in the late 1950s up to 2003, they taught this course or something like it every year. So to have something like that sort of, you know, move out of your curriculum leaves and it leaves a big hole.

Jeremy Nelson (09:02):

Right, right. For sure. So what if, what have students been doing since 2003 or however you filled that, that part of the curriculum?

Brendan Kochunas (09:09):

So I, I’ve heard, I don’t know all the details, but for a while the faculty tried to sort of teach the course. Um, and then the students would sort of go on a field trip to reactor at, at another university or somewhere. That was kind of one thing they would do. And that, but that only lasted for I think a couple years before. Um, they, they sort of stopped with that and then after that, you know, I don’t, I don’t think there’s a big push to try and replace it with anything. I think the department was really trying to broaden its research expertise into sort of other areas of nuclear engineering outside of reactors. And so since then, you know, I think the department’s made a lot of good developments in kind of, uh, the other areas of nuclear engineering in the last 10 years, 15 years.

Jeremy Nelson (10:03):

So, you know, maybe for our listeners to frame the project. So, you know, what are you imagining us building when we’re done with this project? You know, we’ve got a, could you just describe it a little bit more, maybe your vision of how you see this virtual Ford reactor. What does it look like? What is, what can a student do? What can folks learn maybe how differently than they had to and the real reactor where sometimes maybe things took a day or two to reset. Not that many people could be in there.

Brendan Kochunas (10:34):

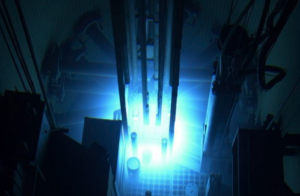

Yeah. Right. So, certainly there are challenges with the, the real facility. You know, that the reactor was, was, had other sort of operating missions that it was doing it, you know, operating round the clock, nonstop serving other research related functions. And so these experiments that the students would do as part of the course were, you know, Oh, it had to fit around and within this reactor schedule, what we’re trying to do with this project is really create an immersive, um, virtual reality environment. So that, you know, when you, when you put the VR goggles on, you’re sort of stepping into the Ford nuclear reactor facility as it was, and eventually be able to interact with it in most of or all of the same ways that you could, uh, in reality of course, you know, being in virtual reality where we’re afforded the opportunity to go beyond regular reality.

Brendan Kochunas (11:37):

Right? So I think, I think we’re targeting some unique experiences in that sense of, you know, letting the students really move to places they couldn’t in the real facility. So, so the real facility it’s this reactor might’ve been about like a four foot cube, sitting at the bottom of a 20 foot pool of water. And so really the only way, you know, you could see it was from the top of this pool. But now, you know, I think one of the things we’ve been talking about is how do we get, you know, the students and experience where they can get right up next to this thing. Um, and, and of course, you know, in real life you can’t see a lot of types of radiation, you know, that you need something else. But in this, because it’s a virtual environment, you know, and we’re very experienced at simulating radiation, we’ll be able to sort of create visuals for the students to let them see, you know, the distribution of things like the neutrons and the reactor. And, you know, I think to be a good nuclear engineer, you kind of have to be able to think like a neutron and, and, you know, being able to kind of see how they move based on physics, and things like that sort of helps ground that intuition. So, you know, as they move on in their careers and they’re dealing with systems that use neutrons, they’ll have a very good intuition about, you know, as an engineer how to, how to build those systems and operate those systems.

Jeremy Nelson (13:10):

Oh, that’s super exciting. Yeah, we were, when we were reviewing the proposals and we saw this as a, you know, a huge opportunity to create something very unique to Michigan. Very special, you know, uh, important to the education of the students that go to school here. And you know, like, like you said, bringing unique opportunities that you couldn’t bring in real life. Like, you know, you wouldn’t go to the bottom of the reactor pool in real life. Um, well, not for very long. Uh, so yeah. So, you know, just we’re talking about a lot of exciting things. We’re talking about what’s possible in the future, you know, do you have any concerns of, of this type of technology for teaching and learning or just things that worry you or, or what we should be keeping an eye out for as we go forward?

Brendan Kochunas (13:55):

I guess my main concern is, you know, what, will I be able to live up to this challenge? Right. So I just, I’m putting it all on me, I guess. Um, but, uh, when I got to Michigan, it was after this facility had been decommissioned. So I’ve, you know, I’ve never been inside of it. Being able to tell, you know, how close to this was reality, you know, what did this part of the building or this piece of equipment look like, how did it operate? You know, I, I don’t have a lot of that firsthand experience. Unfortunately, I think that the timing here is, is, you know, just kind of coming in as late as it could be perhaps. Uh, you know, we still have a lot of folks in the department that have been around long enough that they have this working knowledge, but, you know, we’re more of them are entering into retirement year by year. So that institutional knowledge that we have or kind of nearing the, the window of, we can take advantage of it. So, um, being able to rely on them to fill in a lot of the gaps, uh, for me and the, the team that you’ve put together that’s working on this project I think will be critical to its overall success.

Jeremy Nelson (15:06):

Yeah, no, I’m excited to see their reactions or have them experience it and, and, you know, bring up stories or, or other memories that they’ve had and, and help us shape it appropriately.

Brendan Kochunas (15:18):

Yeah. Yeah. It’s a lot of fun talking with them because they, you know, they have a lot of good stories of things you just never would have realized otherwise. You know, they, they had, if we got time, I’d like to jump into one I heard from one of our emeritus professors, Ron Fleming, who taught this course for, for a number of years, but, um, they used to have, I guess, this real time, neutron imaging system. And because this was, you know, something that had been paid for by Ford, Ford was given the opportunity to use it for certain things. And so back, I think in the, maybe in the seventies when they were developing automatic transmissions, they were having a lot of trouble with, you know, the, the performance of them. Um, you know, they would just kind of break and the engineers really struggled to figure out why.

Brendan Kochunas (16:13):

And you know, there are these completely closed systems you can’t see inside of them. And you know, you, I mean to, to understand how they work, you kind of have to picture all of it in your head. And you know, automatic transmissions are some of the most complex things that humans have ever designed. And so what they did is they took some of these down to this neutron imaging system and, you know, basically shined a light on them, light being neutrons. Uh, and then they were kind of able to see, you know, how the transmission fluid was moving through the transmission and how it worked in operation. And then very quickly, uh, automatic transmissions became a lot more reliable.

Jeremy Nelson (16:56):

Huh. That’s, so that was pretty unintended consequence of the reactor and the environment here, I’m sure.

Brendan Kochunas (17:03):

Yeah. Yeah. I’m sure Ron has a lot more details around that story, so I’m just, you know, he told me that and I’m doing my best to paraphrase his words.

Jeremy Nelson (17:12):

Yeah, no, I wonder how much that helped advance kind of the automotive industry, others follow suit and learn from that. So that’s pretty, that’s pretty cool. That’s exciting that it’s local here as well. This obviously will help enhance the education of a Michigan student. What else do you want to see us do here at Michigan in terms of using XR technologies to enhance the education of students?

Brendan Kochunas (17:33):

Yeah, I think, I think there’s a lot of opportunity, you know, the way I think of it is anytime you’re sort of I guess I’m coming at it as an engineer, but anytime you’re sort of working with a technology or a system that is either, you know, too large or too dangerous or, um, has dynamics that you know, exist on a timescale well beyond human life, these are all unique opportunities I think for XR technology. So, you know, some examples would be combustion systems, airlines turbines, a lot of things in space can’t really go up to space easily. Yeah and you know, cosmological evolution of planets and stars and galaxies, you know, those exist on very long timescales and things like climate change too, you know, those exist on very long timescales as well. So being able to sort of experience, uh, in a way the science of those fields I think, is something that uh, extended reality can bring that, that other technologies can’t.

Jeremy Nelson (19:00):

No, I agree. Yeah. That’s super exciting. It gives us a lot more projects to work on and ways to bring this at scale. So, um, no, that’s great. No, I really appreciate you spending some time with us today and sharing about your project and helping us shape the futures. Thank you so much.

Brendan Kochunas (19:17):

Oh, you’re welcome. It’s been a pleasure.

Jeremy Nelson (19:19):

All right. Take care.

Brendan Kochunas (19:20):

Alright, you too. Jeremy.

Jeremy Nelson (19:23):

Thank you for joining us today. Our vision for the XR initiative is to enable education at scale that is hyper contextualized using XR tools and experiences. Please subscribe to our podcast and check out more about our work at https://ai.umich.edu/xr.