Sean Corp, Content Strategist

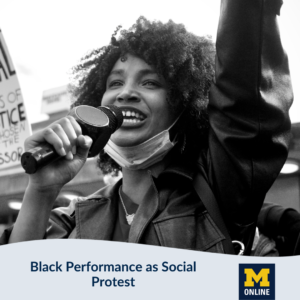

An online course from University of Michigan faculty invites learners to explore the history of social protest through black performance, and expand their understanding of how African Americans have used performance as a source of activism and as a response to injustice from slavery and lynching to incarceration and disenfranchisement.

The course, Black Performance as Social Protest, is taught by Anita Gonzalez, formerly a professor of theater at University of Michigan and now a co-lead of Georgetown’s Racial Justice Institute. Joining Gonzalez is U-M professor of music Louis Toppin and U-M associate professor of music Scott Piper, both of the School of Music, Theatre and Dance.

It was developed over the course of the past two years, and the faculty team’s interest only intensified as social protests dominated the summer of 2020 and the Black Live Matter movement reached new engagement and support.

“I was familiar with the sounds of the protests of the 1960s, and I was interested in how these current protests sounded different,” said Toppin about the development of the course and telling the story of performance as protest through a historical lens and connecting it to modern movements.

The course charts the African American experience through historical contexts. Today, Gonzalez said, there is a new, receptive audience hungry to learn. African Americans are interested in their history, white people are interested in a renewed understanding of the historical developments in social justice, and global artists and performers are interested in interested in learning how their art can support local social justice movements.

“It’s like people’s eyes are open to history and to an experience they didn’t know they were missing,” Gonzalez said.

Video caption: Associate Professor Scott Piper reads an excerpt from Rachel by Angelina Weld Grimke, the first staged play by an African American writer and the first performed by an all-Black cast.

The five-week course charts the history of performance and protests starting with songs sung by slaves, the gullah traditions on the plantations of South Carolina to prison songs from Parchman Prison Farm in 1947.

Next, the course charts the mass migration of African Americans from the violence of the rural south to northern cities where they faced racial discrimination, lynchings, Jim Crow, redlining and more.

The course then explores collective performance surrounding the Civil Rights movement and Black nationalism, including the rising voices of celebrities and civil rights icons, before moving on to exploring more contemporary artistic responses to violence, police brutality and systemic racism including the Black Lives Matter movement.

“Even the creation of this art is a form of protest,” Piper said. “My hope is that people begin to understand the act of creating and what it allows, what it fosters and what it challenges.”

The course provides articles covering historic performances and key historical events and asks learners to reflect on how art and activism are used as a means of survival and of hope and joy in Black communities. Learners are also asked to produce a reflective manifesto for achieving racial equity through performance.

Enroll Now | Black Performance as Social Protest on FutureLearn

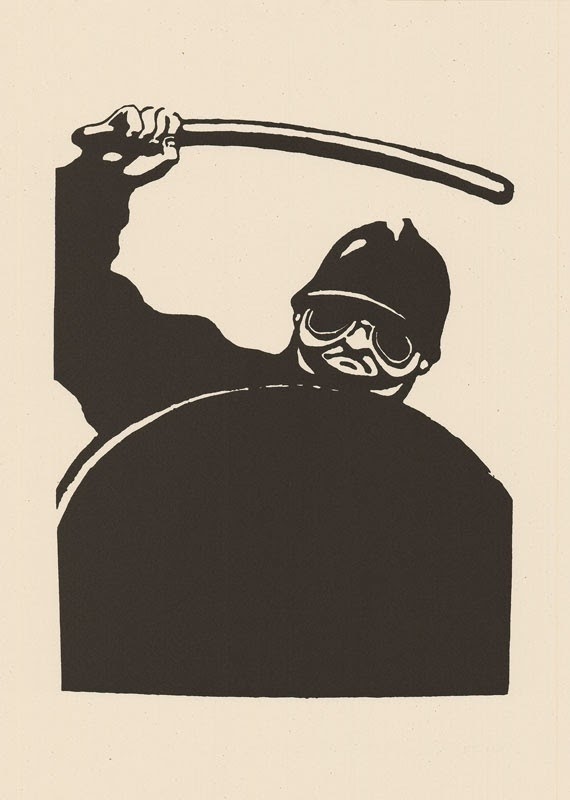

The Whip. The Noose. The Fist. The Baton. The Circle.

Through each week of the course, learners are first shown a guiding image — an evocative and provocative image that helps contextualize the learning for that week and asks learners to begin by reflecting on what they see.

The images themselves and the course content and topics and themes throughout the five-week course may be distressing or re-traumatizing to some learners.

It is important that you are aware of your limits when confronting the course content and manage your participation accordingly.

These guiding images are featured below, including the questions learners are asked to engage with and reflect on in the FutureLearn course.

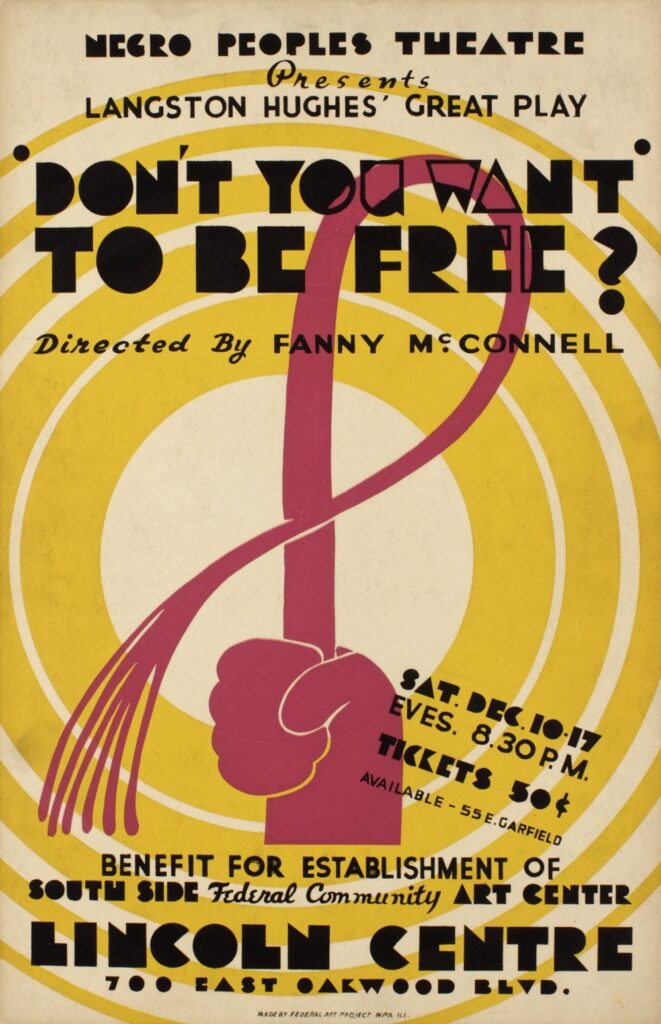

Week 1: The Whip

Included below is a poster for Langston Hughes’ “Don’t You Wanna Be Free.” It was performed in 1938 at the historic Lincoln Center located in Chicago, Illinois, USA.

In Black history, the whip is an extremely visceral image. Whips have been used to represent violence, abuse, and tyranny. Moreover, the whip represents power and control. This image guides Week 1 as the course focuses on slavery and the roots of Black performance and resistance in the United States.

What strikes you about this image? What is its meaning in your cultural context? Does it depict violence? Who do you think the victim might be?

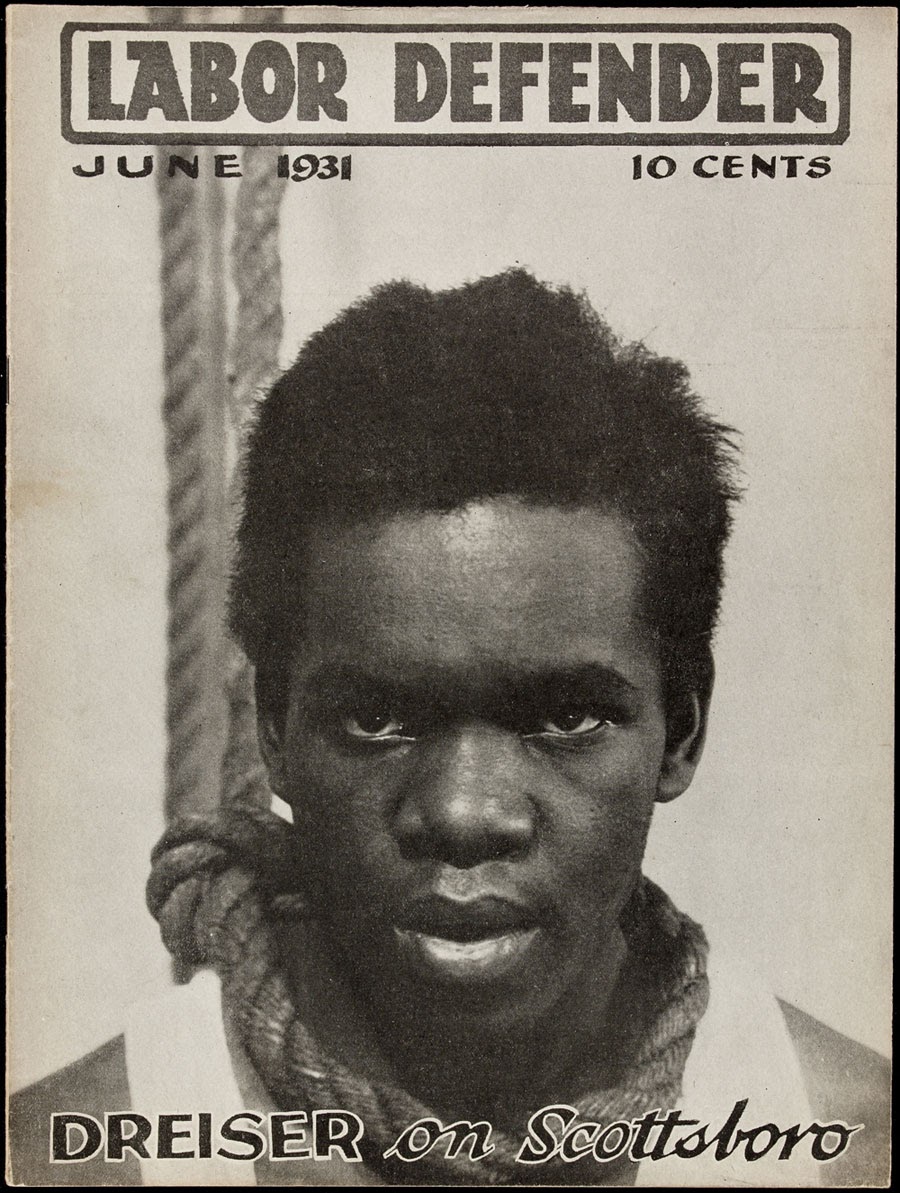

Week 2: The Noose

Above is an image of the front cover of Labor Defender referencing the Scottsboro Boys. The Scottsboro Boys were nine Black teenagers accused in Alabama of raping two White American women on a train in 1931. The landmark set of legal cases from this incident dealt with racism and the right to a fair trial. The cases included a lynch mob before the suspects had been indicted, a frameup, all-white juries, rushed trials, and disruptive mobs. It is frequently cited as an example of an overall miscarriage of justice in the United States legal system.

What strikes you about this image? What is the meaning in your cultural context? Does it depict violence? If so, who do you think the victim might be?

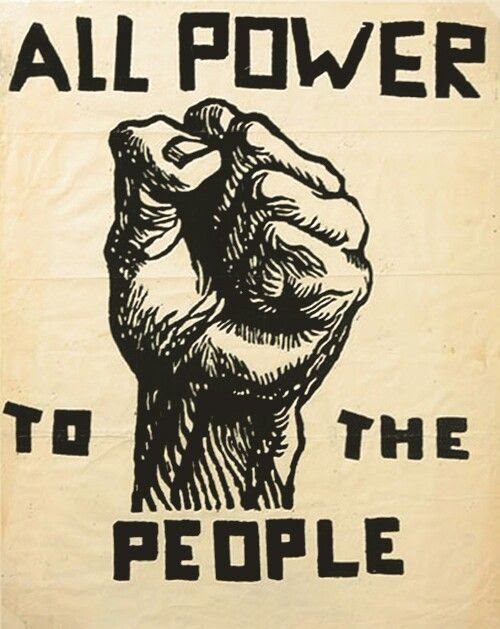

Week 3: The Fist

In week 3, the fist as an image has long represented rising up and fighting the status quo. This image has the phrase “All Power to the People” which has roots in socialist movements and became a distinct phrase associated with civil rights and the Black Power movement.

What strikes you about this image? What is powerful about the fist?

Week 4: The Baton

The baton has historically been, and is still a symbol for oppression and police brutality –a major theme in Week 4 of the course.

About this image: “In 1968, massive worldwide demonstrations protested the Vietnam War, imperialism, consumerism, police violence, and other issues. The largest took place in France, beginning with students in Paris and quickly spreading into factories. 11 million workers—more than 22% of the total population of France at the time—went on strike for two continuous weeks in May. University administrators and police forcefully confronted students occupying their universities and workers engaged in wildcat general strikes across France. Art students, faculty, and staff from the École des Beaux Arts (School of Fine Arts) established the Atelier Populaire (the Popular Workshop). In an unprecedented outpouring of political graphic art, they produced hundreds of silkscreen posters, including the one shown here. May 1968 is still regarded as a cultural, social, and moral turning point in the history of France.”

What strikes you about this image?

Week 5: The Circle

The final guiding image is the Circle, an image that we began noting the importance of and will end doing the same. Circles can also be imagined as spheres of influence.