Ellen Kuhn, Public Engagement Specialist

Elyse Aurbach, Public Engagement Lead

@ElyseTheGeek

One goal of the Conceptualizing Public Engagement (CPE) series was to surface and better understand the diversity of efforts that exist across the public engagement landscape at the University of Michigan (U-M). U-M has a rich history of engaging with publics in a variety of forms, from large interdisciplinary initiatives to individual disciplinary projects undertaken by passionate faculty or staff.

We also wanted to begin collecting all of these public engagement efforts into a larger conceptual framework, utilizing the aspirational definition of public engagement created during the CPE series as a starting point. If public engagement is the “intentional and mutually beneficial interaction between members of U-M and external individuals or groups that results in positive societal change,” what practices are fundamental to any public engagement effort? Which approaches are specific to a particular type of engagement? What connects or differentiates public engagement in K-12 educational settings from engagement in the policy sphere? Moreover, what can these different approaches learn from networking with one another?

The CPE series invited public engagement practitioners from across campus to come together, discuss their own types of public engagement work, and consider ways to organize all of these efforts systematically. Based on these discussions and feedback–particularly around issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion–we have developed a draft Michigan Public Engagement Framework.

By inclusively capturing and reflecting the wide variety of university public engagement efforts, we hope to inspire opportunities for continued support, new growth, and innovative creativity across the entire public engagement landscape at U-M.

The Draft Michigan Public Engagement Framework

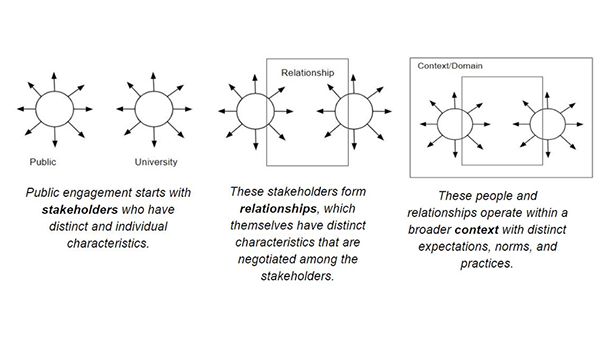

The Michigan Public Engagement Framework rests on three elements: people, relationships, and context. In describing these three elements, we can begin to understand the unique facets of any engagement effort, as well as consider points of similarity. The framework can also be used to prepare for and guide engagement efforts.

Step 1: People

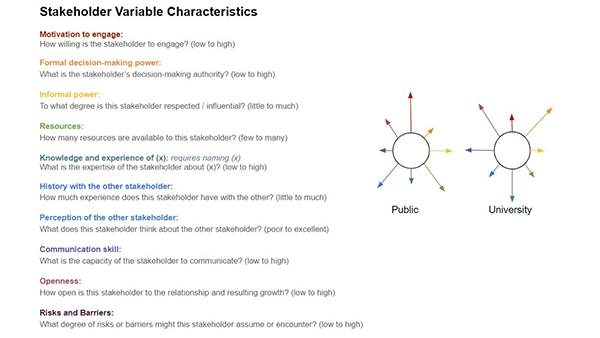

Both public and university stakeholders bring distinct and individual characteristics to the table. How might we describe all of the parties involved?

Some characteristics are relatively static, including demographics, values and beliefs, historical contexts and inequities, group size, and group similarity. These are often the characteristics that are referenced when considering an audience.

At the same time, people also bring a set of variable characteristics that might change over time. Describing and measuring this same set of characteristics for each stakeholder is likely to yield very different–and very informative–sunburst images. These pictures enable us to think more deeply about stakeholders as whole humans.

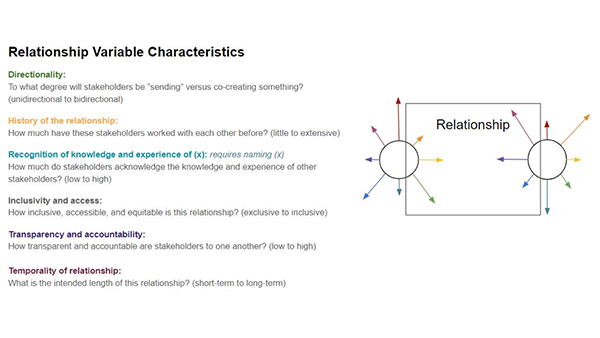

Step 2: Relationship

Similarly, any relationship that public and university stakeholders create also has descriptive and variable characteristics. Descriptive characteristics include needs, goals, and locality, while variable characteristics help us dive a bit deeper. Critically, these characteristics can and should be negotiated between all stakeholders as part of the relationship-building process.

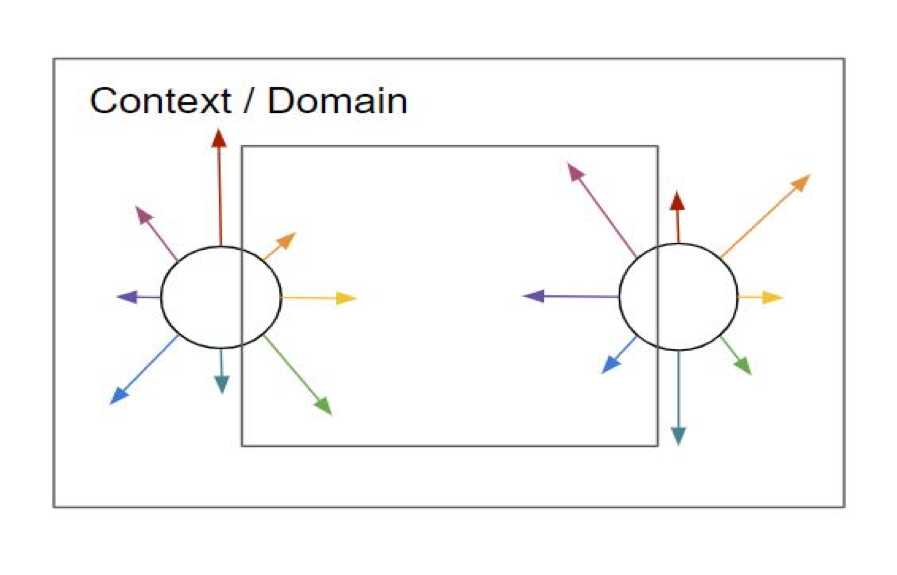

Step 3: Context

The environment in which the relationship exists determines additional norms, expectations, constraints, and opportunities. In the Michigan Public Engagement Framework, we call these “domains.” Domains are often separated by different types of goals, stakeholders, experiences, or content knowledge. Many of them, however, are intersectional, and a single project could span multiple domains. For example, faculty might create a community-engaged course (Community-Engaged Learning and/or Service) that involves their students working with elementary-school youth in an after-school program (Alternative, Informal, and Lifelong Learning) to create a public work of art (Performance, Exhibition, and Installation). Ultimately, these domains help us to conceptualize the range of opportunities available in the university public engagement landscape.

| Domain | Working Definition | Examples |

| Alternative, Informal, and Lifelong Learning | Connecting with learners of all ages in informal or non-traditional educational settings |

|

| Applied Practice and Consulting | Offering professional services, often on a pro-bono basis |

|

| Business and Entrepreneurship | Collaborating to create new products, services, or innovations |

|

| Capacity-Building Programs | Training and enabling stakeholders |

|

| Communications and/or Media | Sharing research-related information in various forms |

|

| Community-Engaged Learning and/or Service | Working directly with external stakeholders through academic courses, co-curricular programs, or volunteer projects to address community-identified needs |

|

| Community-Engaged Research | Working directly with external stakeholders on projects that address community-identified needs and drive research |

|

| Holdings and Collections | Acquiring and negotiating physical assets held by the university |

|

| P-14 Education and Educational Outreach | Connecting with youth in formal school settings or educational programs |

|

| Performance, Exhibition, and Installation | Creating spaces or artistic works open to public consumption |

|

| Policy, Advocacy, and Government Relations | Engaging with all levels of government in order to inform policies and decisions |

|

| Residency Programs and Internships | Embedding individuals within an organization for exchange learning and work |

|

How might we use the Michigan Public Engagement Framework?

We believe that the Michigan Public Engagement Framework allows us to accomplish a number of interrelated goals. First, it allows us to utilize a shared language and framework when discussing public engagement. This in turn helps to name and break down silos that might exist between different types of public engagement activities.

Second, it points toward key practices in public engagement and enables stakeholders to identify and develop skills necessary for effective engagement, including effective communication and inclusive practices. It helps new practitioners in particular to understand the variables of public engagement, as well as consider the wide range of opportunities that are available to them.

Finally, the framework can inform assessments of public engagement activities by pointing to important relational variables and different areas of impact. Practitioners have long grappled with ways to evaluate public engagement activities, and assessing these activities with a common language would help to recognize and reward the important work of engaging with publics.

For a more detailed description of the draft Michigan Public Engagement, including fictional examples of the framework in action, please see this working slide deck.

Where We’re Going

Future posts in this series will outline some coordinated projects and actions that our community is taking to address and overcome barriers to public engagement. Please look for additional posts about the CPE series with the following schedule, subject to evolution:

| April | Next steps |

—–

This post is one part of a set recapping the Conceptualizing Public Engagement series:

Update: We have changed our schedule slightly from the dates originally provided. We will be finishing this recap of the CPE series in May with a final post outlining next steps. Please stay tuned.

- Post 1: Recapping the Conceptualizing Public Engagement Series: Part One

- Post 2: Recapping the Conceptualizing Public Engagement Series: Part Two

- Post 3: Recapping the Conceptualizing Public Engagement Series: Part Three

- Post 4: Coming in May!

If you missed the CPE series but would like to get involved with the conversations and work moving forward, please email us.

**The Conceptualizing Public Engagement Series was sponsored and co-hosted by the Office of Academic Innovation, the Vice President for Communications, the Vice President for Government Relations, the National Center for Institutional Diversity, the Office of Research, and the Vice Provost for Global Engagement and Interdisciplinary Academic Affairs.