Jeremy Nelson, Director of XR Initiative

In this week’s MiXR Studios podcast, we talk with Bryan Alexander, a senior scholar at Georgetown University and alum of University of Michigan. Bryan completed his English language and literature PhD at U-M in 1997, with a dissertation on doppelgängers in Romantic-era fiction and poetry. Over the last 20 years, Bryan has worked to bring digital technologies to small colleges and universities Since 2013, he has consulted with higher education in the U.S. and abroad about the future of higher education.

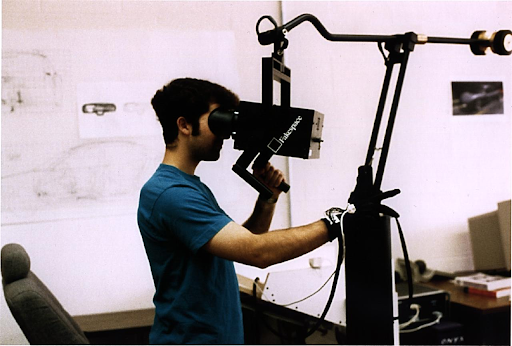

Bryan’s journey with XR started at U-M back in the early 1990s when he was a graduate student. While studying in the English department, he saw virtual reality as a great medium for storytelling. He was able to visit a visualization CAVE (Cave Automatic Virtual Environment) on North Campus that was doing work with the US Navy and an automobile company. In that virtual space, they were able to don a helmet with an articulated arm to visualize and walk through virtual spaces. That led him to a group of students that had built a homemade VR setup in their Bursley dorm room, and he was hooked on the possibilities of the technology.

We discuss a wide range of topics around VR and the challenges to understand how best these technologies can support student learning and faculty teaching. The social VR implications for society and creating connections are fascinating. The technology is in such early iterations, and the possibilities are endless. The time it takes to create high-quality VR applications and experiences is long and the tools are still evolving, so we have a ways to go before more people can begin to create content. We talk about access and equity for students across a broad spectrum of curriculum from nuclear engineering to nursing to medicine and even English.

Bryan shares his thoughts on how the more realistic a virtual environment or an avatar is, the more we are unable to identify with it. He compares this to comics and literature and how techniques of design and writing can allow the participant to fill out the backstory of the character and make that needed leap. We move into a discussion about the future of XR and how Bryan thinks about how we will move through this hype cycle and what we should do here at the university.

Bryan shares his thoughts on how the more realistic a virtual environment or an avatar is, the more we are unable to identify with it. He compares this to comics and literature and how techniques of design and writing can allow the participant to fill out the backstory of the character and make that needed leap. We move into a discussion about the future of XR and how Bryan thinks about how we will move through this hype cycle and what we should do here at the university.

I thoroughly enjoyed my conversation with Bryan and appreciate how he thinks about XR technologies and how to apply it more broadly than just STEM. Please share with us what you would like to learn more about in the XR space at [email protected].

Subscribe on Apple Podcast | Spotify

Transcript: MiXR Studios, Episode 13

Jeremy Nelson (00:05):

Hello, I’m Jeremy Nelson. And today we are talking with Bryan Alexander, senior scholar at Georgetown University and founder of Bryan Alexander consulting, and a three time alum of the University of Michigan. We are talking about his history with VR at Michigan, his work in science fiction, how he thinks about the future of XR coming up next in our MiXR podcast.

Jeremy Nelson (00:36):

Hello, Bryan. Welcome. Thank you for joining us today.

Bryan Alexander (00:39):

Greetings Jeremy, thank you for having me.

Jeremy Nelson (00:41):

Yeah, I’m super excited for our conversation. I’ve been looking forward to it. I’d love to kind of hear your story or your roots back to Michigan and your journey through XR and emerging technologies and kind of share that with our audience.

Bryan Alexander (00:56):

Well, I’m glad to, I mean, as someone with three, count of three degrees from the University of Michigan, I’m always happy to reconnect with Ann Arbor.

Jeremy Nelson (01:03):

Oh, that’s great. That’s great. Yeah. So how did, how did you get into the emerging tech space? I mean, I see you’re, you’re working in English. How did you make that arc and that journey and where, where did that

Bryan Alexander (01:14):

Well, it seemed like an obvious link to me. I mean in part because I’d always been a science fiction reader and I’d always been really curious about the future and like to imagine different possibilities. And in the early 1990s, when I was a grad student, I started thinking about ways of using then emerging technologies to improve students’ writing and for classes and also ways generally they just seemed fascinating to me intellectually. I thought, especially in 1993, 1994, when the web appeared, I thought this is a great medium for telling stories. And I think English should be all over it. And it took 20 years for English to catch up. But but you know, it was, I was looking at all kinds of stuff, you know, thinking about my first publication was actually about students doing peer assessment via email.

Bryan Alexander (02:04):

You know, I had the one crazy semester I was teaching my students file permission, formats and Unix, so they could exchange files or Michigan servers. Right. But VR VR made a lot of sense to me. I mean, it appeared in science fiction back to the seventies actually. It appears in movies in the eighties, of course, you know, think of something like Tron or and, and, but he was you know, we started seeing some early tech and I was, I was hoping to use it in different ways. So my last year as a grad student this was 95, 96. I had a senior seminar, senior seminar yeah, senior level seminar on literature. And I, it was for me, literature on Gothic and cyberspace. So it was, it was a lot of fun, lots of great stuff.

Bryan Alexander (02:48):

And one part of it was we got to look at VR, so we read some fiction about it, but also up on North campus there was this little lab tucked in a hill and it had been funded, I believe by combination of the US Navy and a car company. And they were looking into VR. So it was wild. I know nobody I knew on main campus had ever heard of it. But you know, it’s a huge university. So I took the students up there and got them to explore. So they had a cave, you know, capital C capital A capital V capital E. You know, I think it was the floor of the ceiling and two walls, a visualization. And then next to that, they had a lab where you could put on a big helmet. And I think that the helmet was mounted in the ceiling through, you know, a articulated arm.

Bryan Alexander (03:35):

And you had one or two devices. I don’t remember if they were gloves or pucks and you got to walk around and it was you know, the students were very excited by this. This was a, you know, a big paradigm shifting experience. And one of the nice things about it was they got to analyze it, reflect on it, thinking about and thinking with all the different intellectual tools that we’ve been deploying this semester. So that was, that was pretty exciting, but what really blew me away was the end of the semester. Two of my students have built a VR project in their dorm room. I think this was, I’m trying to remember which dorm this was. It was on North campus. It was Bursley.

Bryan Alexander (04:16):

And so I had to go to their dorm room and they had, they built this setup, you know, complete Homebrew. They had a you know, a headpiece they had a puck, it was all, you know, lots of duct tape, four or five different computers. CPU breadboards everywhere. And they had downloaded a a game level and for a 2D game and they’d hacked it up and made it into a three dimensional environment and they use it to kind of make an argument about some of the readings of the class. And it was fantastic. And so this is again in the mid nineties, the great first wave of VR.

Jeremy Nelson (04:52):

Sure.

Bryan Alexander (04:53):

And so I I’ve, I’ve, I’ve been fascinated by it ever since. And when that wave crashed around, you know, circa in 1999 or 2000 you know, that was all there. Ready to go. So now that we’re in the second big wave you know, I could reach back and draw on that Michigan experience.

Jeremy Nelson (05:10):

That sounds like some of the experiences I remember being a freshman on campus, I think we might’ve overlapped just briefly. I started as a freshman in 96 just about a year then yeah. In computer engineering. And, and didn’t find that space yet. You know, we, we have a VR lab, a visualization studio now that’s quite a bit bigger about 30 workstations and sit, stand desks and Oculus rift and Vive pro and a lecturer stand up front. So, you know, similar though, concept of creating a maker space where, where students, faculty can come and design and build and take it from there. So but still a lot of folks don’t know that exists or it’s open to them from central campus. You know, the great divide of that short bus ride.

Bryan Alexander (05:59):

Absolutely. I’ve, I’ve, I’ve walked that several times and over, over the years and we actually, my wife and I got married right near that edge. We got married on the Island park.

Jeremy Nelson (06:11):

Oh, nice.

Bryan Alexander (06:12):

Yeah, yeah.

Jeremy Nelson (06:14):

Yup. I’ve spent, I spent some time there with the kids running around and things like that and kayaking, canoeing down through that area. On the Huron river for sure. Well, yeah, I mean, it sounds like you’ve been involved from the beginning. Where did that journey take you after you left Michigan? Or when did you, you come back to VR?

Bryan Alexander (06:36):

I became a professor at a small liberal arts college in Louisiana called Centenary college. And I mean, one of the ways I actually got the position was because of my experiments explorations in technology. So from around the early nineties, the humanities job market has just been terrible. We’ve we’ve flooded the market with really well credentialed PhDs, and we’ve cut the amount of positions available. So, you know, I was there, I had a degree from a world class institution, but there were hundreds like me. But I could say, yeah, I’ve done stuff with MOOCs and buds and VR, and you’re like, Oh, come on. You know, this is extending apart. And so I constantly worked on on emerging technologies then you know had all kinds of stories. I could tell you about digital audio about computer gaming, but information literacy about struggling

Bryan Alexander (07:27):

With campus IT, horrifying my fellow humanities professors and exciting them. And I ended up starting a program in information technology studies, but then I left the college. I got hired away by a nonprofit that focuses focused on small liberal arts colleges. So it, it was a nationwide organization. So you know, in Michigan schools like Albion, for example, or the hope college and I moved to Vermont where it was based. And I worked with ultimately about 300 colleges and universities doing emerging technologies for them trying to show how they could be used in the small private college world and did that for a decade. And it was very, very exciting. And so if you think this is circa 2002 to 2013, you know, the emerging technologies then were what we called web 2.0 now, social media mobile devices.

Bryan Alexander (08:21):

Cause you know, the, the Kindle and the iPhone only appear around 2006 or so, right. Talking about gaming and you know, and all kinds of great stuff. And there, wasn’t a lot of interest in VR. I mean, there’s a lot of interest in if you want to DVR. You mean, you think about say at the time say second life, which had its moment. But I track the field very closely. And then after working with that chunk of higher education, I launched my own business to work with all of higher education. So I work with community colleges with universities, research universities, military academies. I also work with governments associations and companies, you know, anyone interested in the future of higher education. And when the, when VR started coming back with Oculus and when Facebook bought it, and then with new startups, like magic leap then I just, I just kept running with it.

Bryan Alexander (09:15):

I, I kept researching and trying out new things. And then at Georgetown university had been teaching a few classes there over the past couple of years and my students have been fascinated by this and they’ve got a terrific, terrific lab set up in their library which has a great amount of gear called the Gelardin center. And they’ve got wonderful people, lots of hardware, lots of software, you know, onsite or to check out. Yeah. And it’s great. So I’ve been having my students try this out and I could tell you all kinds of stories, what they found and how they react. I’ll tell you one, one quick tip though. My favorite app to teach students, to get them to use right away by far is Tilt Brush.

Jeremy Nelson (09:59):

Yes.

Bryan Alexander (09:59):

Just that’s, that’s the one which says this is not just an upgrade of what you’re used to. This is a different world. And I usually have to pry the students out of it because they get so immersed in it. So caught up in drawing and moving things and then walking around and through what they’ve drawn. It’s just you know, it’s just fascinating.

Jeremy Nelson (10:20):

It’s a wonderful tool. Yeah. I’ve had my children try. I mean, they love to draw, they’re little five and eight. And like I had to, I’ve had to like, they’ve killed the battery they’ve been in there. So they’re laying on the floor and they’re like Michelangelo drawing on the. Like they’re just laying and drawing and walking around, like, but very quickly to like, take to that space of like how you can walk through your drawings.

Bryan Alexander (10:42):

Yeah. It’s remarkable. We have I’ll tell you, my first book that I published was on digital storytelling and that emphasized creating stories with audio, with video, with computer games, with social media, and then the second edition I was able to add a chapter talking about what does it mean to tell a story with VR and that’s, that’s still an emerging topic. We’re still trying to figure this out. I’m endlessly fascinated by it as are, as are, my students, you know, what are the, just like film has a different way of telling stories than TV than versus computer games versus print versus radio it’s you know, VR has its own rules. And as we mutate VR into XR, you know, blend in the augmented reality part, you know, we still get it. It’s, it’s fascinating. I mean, it’s like, we’re, we’re in the age of Edison right now with moving pictures, trying to figure out, you know, can we actually pick up the camera and move it? Wow. That changes things.

Jeremy Nelson (11:40):

Right. Right. Or what’s the normative context or what’s the, what can we do with the interactions? Like what are we? UI were having a conversation this morning with our development team. Like, so what, so what’s the standard UI in this space, right? We have 30, 30, 40 years of web or like computers, but like, is this, can we do a watch? Do you hold a tablet? What do you, what do you do? And it’s just still, we’re all exploring.

Bryan Alexander (12:05):

I just got, got my hands on another headset. And I just, I was going through STEAM and downloading a bunch of different demos and some some different levels, or games, we didn’t have a good noun for this. Right. Is it a VR object? You know,

Bryan Alexander (12:24):

Wait, we need a noun for this, which is, you know, when something new shows up and the language doesn’t settle around it easily. For me, that’s always the sign of the future coming into focus. I mean, like when Twitter took off, you were like, well, what is it? Is it micro, blogging? No, it’s just Twitter. We can’t come here.

Jeremy Nelson (12:42):

Right. Right. So it becomes a verb,

Bryan Alexander (12:45):

But, but so going, going through all these different objects or levels, and one of the things that struck me was each one, basically it had its own UI. There was almost nothing in common. Is it really 360? Does it force you into a dashboard? Do they have a, does something require your head motion or your hand motion and what’s your hand motion? Who knows? You know, is it clicking? Is it moving? Is it just touching a, so yeah. These are early days

Jeremy Nelson (13:12):

Where best do students learn. I mean, we’re really interested here with our XR initiative of experimenting, evaluating, trying to understand, you know, where does VR make better sense? Where does AR work? What sort of interactions with them? How much time do you spend? How do you assess, how do you evaluate? Is it just transfer? Is it, how do you assess, you know, is it helping students learn better? Is it?

Bryan Alexander (13:36):

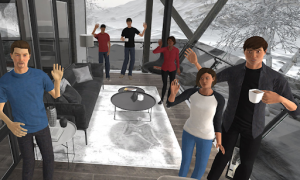

True. And then you think about, I mean, there are a few different pieces of this. I mean, one is, you know, you think about the experience of, you know, students putting on the Google Cardboard or the Oculus or whatever, and then they experience it. Okay. There’s that. We can, we can study that, but then there’s the student as maker. And, and that’s very, very difficult because apart from a tool like, like tilt brush there, it’s very, very difficult to make content for VR and XR. I mean, you’re, you’re looking at, you know, students having to learn Unity or even just making a 360 video that’s nontrivial. And that’s very, very basic. And we don’t have a tool, like, you know, think about all the different web making tools or, or an easy audio maker. Well, like Zencastr right? Or like audacity or or for games, we don’t even have tools like Twine or Game Maker. So it’s still, I mean, that’s an issue, but I guess the third issue is one that we’re still thinking about, which is a major one, which is the, the skew between, is this the individual experiencing the digital environment all by themselves? Or is this a social community activity? And right now it’s almost entirely the former in part, because if you’re face to face with people this is an obstacle. I mean, you’re putting a, you’re slapping your computer at your face.

Jeremy Nelson (15:00):

Right, right. And cutting off the world.

Bryan Alexander (15:02):

I mean, if you and I sit down with an Xbox and we each have our controller, I mean, we know we can see each other. I mean, I can see the controller vibrate in your hands, even as our characters move on screen. Or if I’m playing with my son, I can watch him as he grins evenly and kills me before I can do anything. But, but the other thing is the representation of others is still relatively cartoonish. And but, but it can be, it can be so powerful. Here’s a little story. I downloaded a an app, I guess, a VR app for a bad horror movie. And my PhD was in literature with emphasis in Gothic horror. Someone was looking for scary stories and it was a classic little thing. I put it on. And suddenly I was in this haunted house.

Bryan Alexander (15:44):

You could tell it was a haunted house, cause it was all decrepit. And there are all these creepy sounds. You could hear rats squeaking and the drapes are rotted and you could hear the wind wooshing outside. And in front of me on a kind of decayed, old chair was a scary old woman who was whispering to me something. And the first thing I did was I leaned forward so I could hear her better. And I stopped myself and said, well, that’s stupid. I mean, is this actually audio sensitive for that? No. You know, but, but it was so compelling. And then as I’m listening to her, I hear that creak of a door behind me. So not only do I feel that thrill down my spine, but honest to God, I turn turning around and I point to her and I put my finger up and say, excuse me, I have to answer this. Well, what did I just do? And that was a cheap, you know, not very impressive knockoff. Right. But if I see you sitting there on a bench, it’s so much more compelling, so much deeper than almost any other experience outside of being face to face. So the social possibilities are really potentially huge.

Jeremy Nelson (16:50):

Right. Right. And there’s, you know, a lot of folks are rushing to this space. There’s some interesting collaboration tools. And especially in the world of COVID right now, or, you know, books here, like how can I teach my class in VR? And it’s like, well, maybe it’s going to take, you know, we’re not going to do it in three weeks. You know, it’s gonna take a little more time.

Bryan Alexander (17:09):

Right, right. Right. I mean, it’s, it’s, it’s, it’s so interesting because on the one hand we have all these rich possibilities and yeah. You extend it a little bit further forward and you think, okay. You know, the classic thing for classical studies is to use ancient Rome or ancient Athens and to wander around, I mean, back in the nineties, we did this with muds and moves. And then afterwards there were versions of this with with a web in two dimensions. But to be able to walk around the Parthenon, you know, to look through Nero’s Rome, I mean, this is fantastic, but on the other hand we have, as you said, the production problem where we just can’t, you know, whip this out in a hurry I mean production VR makes 3D printing look like something from Star Trek. And the other, any other problem is we have the digital divide you know, Google Cardboard, I admire deeply as, as an attempt to address that. And it doesn’t get nearly enough credit for it, but these, these head pieces, you know, you’re talking about three, $400 on up, plus the bandwidth. If you’re gonna, I, I often use the New York times VR stuff. If you’re going to download those, you need serious broadband because you’re sucking down a big pile of data. If you’re doing it live, you’re going to be exchanging data back and forth. So again, for the digital divide that’s a real challenge.

Jeremy Nelson (18:29):

Yeah. Yeah. For sure. I mean that’s and just even access to equipment, right. You know, access to headsets from a supply chain standpoint, right. Like they’re being bought and sold out immediately. You know, we’re having lots of discussions about that here of like, how do we start to purchase devices in enough quantity to enable more learners. Right. And then, but to solve that first, I’m like, well, I want to start to solve the content problem or the content barrier, like either acquiring enough content or building content to then make purchasing more headsets, a viable, right. Like up to 200 headsets for one title for one course that is 20 students. Right.

Bryan Alexander (19:16):

Well, I guess this is, this is the other problem too, is that the, and this is always been a problem with educational technology content. And in fact, I would say with publishing any educational content, including in books which is it’s, in some ways it’s much easier to design educational content for an incredibly narrow niche of the curriculum. But it, it has a bigger impact if you can desire something has a larger swath. So, you know, we it’s much more exciting to do something about, say a Byzantine art, right. You know, you can imagine reproducing a Byzantine church from 11th century and that’d be great. And there’s one class, you know, that does that. But if we could do English as a second language, if we could do art 101, then you get a larger number of students. I mean, the, you know, the first VR that does calculus 101 will be a huge, huge hit.

Jeremy Nelson (20:08):

Yeah. I mean, that’s what we’re looking at, you know, kind of a diverse set of schools. You know, VR and XR initiative is supporting all of the schools and colleges here in Ann Arbor and the University of Michigan. And, you know, we’re working with folks in architecture, we’re working with the nuclear engineering program to rebuild the nuclear reactor on North campus. But we’re also looking at nursing and medicine where the scale there has a different, you know, flywheel effect, right. If we can help teach skills or, you know, transform the way they do medical rounds with a HoloLens, let’s say that has huge impact and huge scale.

Bryan Alexander (20:46):

Well, I would say that that’s be one of your big priorities because I mean, you know, there’s the immediate need that, you know, we’re in a pandemic and at Michigan, of course, famously, you know, is you know, it was hit very, very hard, especially in Wayne County, but you also have the perhaps the strongest lockdown in the US last I saw. But the but on the other hand, there’s the long tradition in medicine of simulation, which dates back to well classical times cause it’s always, it’s always easier to use a plastic toy than a human organ. I always find medical and biomedical. I mean the full range of medicine, valid, healthier radiology nursing you know, it’s just simulation is just such a given. I was in Finland looking at a wonderful medical school and they had a whole series of rooms and each room was a different simulation.

Bryan Alexander (21:42):

So one, one was a simulation of birth and they had an elaborate elaborate animatronic doll. Isn’t the right word. You know, a mannequin that would deliver a child. And then another one, they had a, a basic I don’t know, what’s called a, a room full of miscellaneous patients. And some of them were played by actors and some of them are played by animatronics and the the animatronics would be voiced by other students behind a wall. And I was asking him, did they ever tease each other? You know, do they ever like, and but one, and this is something from Michigan, the state, I mean that will be so important. One room was actually a living room. I said, what’s this about, well, this is home care. And so, you know, we have to teach students, you know, who are in scrubs and everything else to go to somebody’s living room. And as our populations, age in Michigan, you know, the aging is accelerating rapidly. I mean, that’s, that’s very, very important. So, but imagine doing this, but without any physical rooms, just having these toggled back and forth on your headset.

Jeremy Nelson (22:50):

Right, right. Yeah. And in any, from anywhere, right. Like I’ve, while we’ve been home, I, you know, I’ve joined, you know, Oh, a virtual OR from folks in the UK and Greece, you know?

Bryan Alexander (23:02):

Wow.

Jeremy Nelson (23:02):

We’ve done collaborative, architectural design reviews from people across the country and across town for their architect. So there’s just, you know, I I’m fortunate. Right. And I have a number of devices here at home. Most folks don’t. So yeah, that divide you mentioned is critical. And as a public institution, you know, we need to make sure it’s accessible and available to, to a wider population. So we think about things like, okay, if we make this virtual nuclear reactor, like how do we make it an accessible, do we make a desktop version? Do we, can we add subtitles? Do we add voiceover? Like how do we, you know, narrate that or make it available? Cause we don’t, you know, if it’s required for a course and certain people can’t experience it, that that doesn’t make sense.

Bryan Alexander (23:51):

I had this fascinating experience today. I was I was on the zoom meeting a presentation about infrastructure. And it was first, I would ask you if you’ve experienced this every speaker and there were five of them introduced themselves with their name and their job. But then they described themselves. They said, you know, I’m a male with pink skin and I have Brown hair and I’m wearing a blue shirt and all of this, I’m standing in front of the chart and I was a little disoriented, Oh, they’re doing this for people who are visually impaired.

Jeremy Nelson (24:22):

Huh? No, I’ve never done that. But now that you say that it’s like,

Bryan Alexander (24:25):

It makes sense.

Bryan Alexander (24:27):

Because you can get the, you get the transcript and zoom now does a pretty good job with that. But, but this leads us to one of two questions for you. One is what do you think of the competition between VR and zoom? I mean, if you’re going to have a social distanced experience video conferencing, I don’t mean just zoom in particular, but zoom in general video conferencing works. We’re all using it right now. You know, I mean, look down the road, say a year, two years, five years, I mean, is, is VR XR really the next stage?

Jeremy Nelson (25:03):

I think it has the potential, right? Like, I mean, some of the things that I just can’t do, I’ve tried to join from VR. Right? Like it gives me a whiteboard, like, but I, when I participate, I sometimes, you know, I’m pulling up a Google sheet, I’m showing another screen, I’ve got a video over here. Like I can navigate so fast through a browser. Right. Pulling up those windows and sharing and typing. And you know, I think until I can get that input faster or I have some sort of keyboard or, you know, I can touch the table and there’s a virtual keyboard lets me type just as fast. I think in some context, you know, we’ll see an iterative evolution. Like we’ve tried the spatial app. Right. You can be in from a HoloLens or from a desktop or from a VR headset and you know, it’s, it’s close.

Jeremy Nelson (25:46):

It has a lot of potential. Right. Like I felt like the person was there. Even these, some of these medical simulation, you know, we met someone from the UK and a physician. He was here in Ann Arbor and I was here like the representation was kind of a translucent head with a mask and a hat, and it was gender neutral. And then just my hands and like kind of just below the neck. So that was the embodiment. And, but it was almost enough, right? Like as you were moving your head that avatar head was moving around and like the hands I could see if they’re at their side and like, it was enough to make me believe that like when I kind of entered the room, I was almost like right on top. My avatar was almost right on top of that other person’s avatar. And I was like, Whoa, like I stepped back. And like, I was like, okay,

Bryan Alexander (26:32):

I think there’s two things going on there and why that’s so powerful. And I just, this week I’ve been doing more with Virbela and I’ve been doing it on my laptop, not, not in VR, but, but still it’s. And I think there’s two things going on. And one is just the simple fact of motion. You know, seeing something move trigger something in the brain. And we’re w w it means it’s alive. I mean, think about some of the telepresence robots, like the double robot or the, a QB and, you know, just seeing someone’s face in a tablet. All right that’s video. But when the tablets swivels or moves back and forth. That triggers something deep in the brain. I think of, you know, a flight or fight or you know, that it’s alive and that’s, it can be uncanny and disturbing, but it has an impact.

Bryan Alexander (27:18):

But I think the second thing is there’s a fantastic, fantastic book about comics by Scott McCloud called understanding comics. And I, for everybody listening, I just recommend just grabbing a copy and reading it immediately. Cause it’s, it’s an absolute delight. The it’s a comic book, it’s a graphic novel. It’s, it’s huge. It’s extremely entertaining and engaging, but not easy. Cause it’s a work of aesthetics in theory, where he tries to explain how comic books work. And it’s just fantastic. I mean, I’ve taught it for years and it’s just absolute treat. The author by the way is just a great content creator in general. So he’s always fun to read, but he has he makes this interesting point. He wants to know why is it that when we have access to photography, why do we like hello kitty so much because hello kitty, it’s just a few lines.

Bryan Alexander (28:11):

And so he does, he comes up with this interesting theory, says that if the more realistic, the more detailed it in computer terms, more pixels that we get for representation, the more we appreciate it, but the less we identify with it because every extra level of detail means it’s an extra level of not us. So if you play Halo and there’s master chief, he’s like, wow, that looks glorious in the light. You can see, you know, fog coming off of his helmet, but that just tells you this is somebody else. But something like Mickey Mouse or the smiley face, or hello kitty is so simple, it’s so easy to inhabit. And you can think about this in literature. There are characters that are so beautifully realized that, you know, that’s Madame Bovary, but that’s not you. But someone like the the heroine of the Twilight books is drawn as thin as possible.

Bryan Alexander (29:07):

I mean like a sheet of paper, she has no characteristics, which is why people can inhabit her so easily. So I, I wonder if I, you know, we see you in that cartoon space in Virbela or whichever one I can fill it out. I can say, Oh, that’s Jeremy, Oh, that’s Fred. That’s not right. But if, if it, if it’s the gorgeous, you know my whole family, we play the mass effect computer game series, which is of course a delight. And when I see the different characters, I’m in awe that’s clearly Bob, the alien or, or this pilot. But maybe the cartoons, maybe they really do work.

Jeremy Nelson (29:47):

Yeah. Right. I mean, you’ve seen the demos for the new unreal engine five and PlayStation, right? Like it looks gorgeous. Billions of polygons looks amazing. You’re like, yeah. They said that same challenge. Well, you know, in terms of, of the future, we haven’t spoken too much about that, but I want to spend a few minutes chatting about what you see as the future of XR, particularly around teaching and learning. And we’ve, we’ve addressed that, I think a little bit through our conversation, but as a futurist, I’d love to hear your thoughts.

Bryan Alexander (30:18):

Sure what I’m seeing right now for teaching and learning. The primary purpose is visualization. Just, you know, the ability to visualize, you know, the DNA molecule Jovian moon the center of a hurricane you know, things that we can’t normally or easily visualize or where visualization is expensive. So to see things from history, to the things from other worlds, and again, different scales to be able to walk through a galaxy or to be able to, you know, move inside of an atom. That’s just enormously powerful. Now for a lot of visualization technologies we know that the second thing is the ability of students to edit or make, to shape that kind of content. So that’s, I think the next big step that we’ve got to get to as much as I enjoy unreal and unity that’s, that’s not an easy, you know, that’s a big lift so we need something better for that.

Bryan Alexander (31:16):

And on top of that, there’s the social aspect where, you know, we right now, because we’re in the pandemic mode remote working is very, very important, but even when and how the pandemic ends, and we don’t have time to go into that right now, but we still are used to remote work. Remote work is still a key part of what we do. So learning to do it through VR may be a pedagogical boon where students can learn how to conduct that. But when it comes to the future, I, I have a lot of hope. And especially for the XR version, I mean, I love that the intertwining of augmented reality and virtual reality Microsoft calls it mixed reality. I like that term too. I mean, I remember reading JD Spore’s pieces in the 1990s when we talked about, you know, assigning information to places.

Bryan Alexander (32:05):

And there’s just a huge level of, of, of creativity. And you think about how much we can, if we can add a laminar layer of, of virtual environments to the surface of the earth, just how much we can do in terms of, you know, having conversations with people of, of having a blank room that we can decorate at once. I mean, we’re, we’re just stepping into that, but my one caution I have is not just the, the digital divide and the accessibility. I mean, those are a huge cautions and we, it’s almost impossible to overstate them, but the other is this is a field that is, is ripe for a hype crash. We have the big, you know, hype crash around 2000 and personally sidebar. I think this is where Jaron Lanier, entire new career comes from being an anti-technology current budget because he was involved in the first wave.

Bryan Alexander (32:58):

He saw it crash he’s never gotten back. I don’t think anyone should read him. I mean, he’s a terrible critic and just an obsolete, horrible writer, but, but he’s he’s, he’s foam thrown up at that first crash. So right now we have billions and billions of dollars invested. And so many things haven’t taken off magic leap had such potential and it’s circling the drain right now. Microsoft HoloLens is a fantastic tool but really they’re, they’re not aiming at seriously consumers. I mean, it’s primarily for businesses.

Jeremy Nelson (33:29):

They have a clear path. Yeah.

Bryan Alexander (33:31):

Yeah. I mean, in a lot of ways we’re waiting for Apple to offer us, you know, a tool and that might not work. I mean, Apple, Apple fans hate to hear this, but Apple offers duds all the time. Apple books didn’t take off, you can think about ping, but, but if they make their magic work and we get some kind of head gear I talked to the science fiction writer, Neil Stevenson about this, and as w what’s what’s the next physical interface, you know, we’ve moved from desktop to laptop, to tablet, to smartphones.

Bryan Alexander (34:03):

And he said, it’s going to be glasses. Okay. Okay. So again, eyeglasses or whatever from Apple. And it goes wide and that Microsoft and Google have their own version. Okay, good. Very good. But we have to get over a hump. I think we will have maybe a canyon to cross and and that’s going to be difficult and tricky, but it may be that VR and XR become the dominant computing paradigm. I mean I’m sitting here talking to you and I, I’m a black box almost literally in a sound booth. But, and I have a headset on, but just from my ears, but if I could cover my eyes and we can meet virtually, and then I could decorate this space with art and media images sounds of all kinds. This is, this is clearly stuff of science fiction, which is why we have to pay careful attention to it. Cause we may be inhabiting that space, not too far off from now. So those are a few of my thoughts for it. I’ll tell you when wa when we’ll know that this has really taken off is when we get the first wave of copyright lawsuits about XR. That’ll be the sign that it’s, that it’s become significant.

Jeremy Nelson (35:08):

That’s a great point. No, I, I love, I love your thoughts. Thank you for sharing that maybe, maybe just to wrap up, what do you, what would you want to see Michigan do in this space? W what advice do you have for us?

Bryan Alexander (35:21):

Oh, full court, a full court press do through everything and what your unit is doing is so great because you’re addressing multiple colleges and units within the university. But you’re also very carefully, I think moving across the curriculum I mean, there are some technologies that are clearly aimed at one chunk of the curriculum. I’m a big fan of annotation software for the web, and that’s almost entirely about the humanities, which is great. I’m a humanist, but it really needs to cross the frontier. You look at 3D printing, which I’m also a big fan of, and that’s almost entirely the sciences. So again, we need to see beyond French teachers printing the inevitable Eiffel tower. We need to have some, some more work on that. And I think that’s one, that’s some vivid advice just for you to keep following doing what you’re doing, making sure that you have VR and XR for English as well as for biology, as well as for sociology.

Bryan Alexander (36:17):

But I, I think get ready for a possible hype crash and to ride that out and to get past it, but then it really lean hard on getting, getting the tools in the hands of students to make stuff. I mean, Michigan is the home of, I know so much innovation. You have so much innovative horsepower, so much computational heft, it’d be great to see what your students and your faculty come up with so that students can make a VR, whatever we call the noun. No we’d love if I can go back to that dorm room in the 1990s, I want to see more of that spirit of Michigan tinkering so that students can make stuff. And so they can start making, not just consuming, but creating the XR world to come.

Jeremy Nelson (36:59):

I love it. Thank you so much. Thank you for your thoughts, advice, and for your time today. I really appreciate it.

Bryan Alexander (37:05):

My pleasure. Thank you for hosting. Thank you for doing this podcast, but also again, thank you for doing this XR work. You’re like a a time traveler from the future and you’re, and you’re helping lead Michigan that way. Thank you for doing that.

Jeremy Nelson (37:24):

Thank you for joining us today. Our vision for the XR initiative is to enable education at scale that is hyper contextualized using XR tools and experiences. Please subscribe to our podcast and check out more about our work at https://ai.umich.edu/xr.