Realism of virtual spaces and participants offers promise for many uses

Hannah Triester, Communications Fellow

Amid the congenial and casual conversation one might expect during the social hour of a conference, one attendee came up to Jeremy Nelson, organizer of the University of Michigan XR Summit in April, and took his breath away.

“He told me this was his first time on campus,” Nelson said of the U-M student who had just completed his first year at the university, learning remotely due to COVID-19. The student’s admission was even more remarkable because this inaugural visit was taking place in a virtual recreation of U-M’s iconic Diag, and he, Nelson, and more than 200 others from all over the world were online avatars chatting with one another.

“I talked with people from Jordan, London, Hong Kong, and Colombia—to name a few,” said Nelson, director of the U-M XR Initiative at the Center for Academic Innovation. Nelson adds that the center later hired the student and another he met at the virtual event as fellows.

One of the benefits of attending conferences, workshops, and the like, is getting to meet others and share information during informal sessions. With most events going virtual the last couple of years these networking opportunities have become a challenge.

As the Center for Academic Innovation prepared for its first annual XR summit Nelson had an idea: create a virtual representation of the Diag for people to meet, using the technology that was the focus of the event.

So, on a Friday he challenged one of the center’s student XR fellows to think about how to present participants with a unique reception that would take place on a virtual U-M campus. By Monday, George Castle, Stamps School of Art & Design student, had created a prototype using Google Earth maps.

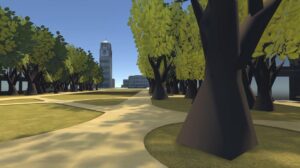

With help from Nicholas Di Donato, a graduate student in the Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning, Castle’s rough representation was refined into an exact replica of the Diag. Armed with Rhinoceros, a design software that renders surfaces and solids into accurate 3D models, they went to work reconstructing the Diag for use as an online social platform, with help from several campus offices.

The pair drew heavily on university resources to help them gather enough information to reconstruct reality. Lauren Plews of the University’s Architecture, Engineering, and Construction (AEC) services became a key player throughout development. Di Donato also got help from Ray Garret at the Facilities and Operations Office, which retains GIS (graphic information systems) data and blueprints for every component of the campus landscape—down to individual trees—and every structure on campus, old and new.

For what wasn’t available or for drawings that were outdated, Di Donato took a trip to Central Campus, filling in missing pieces with fresh, on-the-ground images.

Di Donato’s own Central-Campus immersion—in, for example, the asymmetry of the E-shaped West Hall—was vital to creating the final digital experience. One building at a time, he employed skills acquired in the architecture program to recreate the most minute of structural details.

Castle then fit the pieces together into a cohesive puzzle, using Blender, open source graphics software for building VR worlds.

“He would take my buildings and put them in his overall model. He set up all of the lighting and vegetation, and all of the texture palettes,” Di Donato said. “He really brought the world together.”

The result was a multi-purpose, realistic rendering of the Central Campus nucleus.

“All of the trees are in the right place,” Nelson said. “The students were the creators. I gave them a vision and they ran with it.”

Though the virtual Diag is a technological feat on its own, the project’s virtue is its ability to foster social interaction in real time, he said.

One class used it to “meet” during winter semester, and Nelson sees possibilities for other online learners across the globe who would never have a chance to come to U-M. He also sees potential for admissions, alumni and other groups to use it for an introduction to U-M or a nostalgic return to campus for activities, or for enrolled students to use it for immersion into campus offerings.

“This isn’t a VR experience featuring boxy headsets or people clumsily reaching for virtual items; there is no fancy, pricey equipment being used. Instead, users get a more intimate personal interactive social experience in this virtual environment,” Nelson said. “It’s only going to get better. The technology will improve, the avatars will get better and will develop more ability to sense things.”

Achieving intimacy and accessibility is possible by using AltspaceVR, the project’s host platform—which offers both a Windows and MAC desktop client. Without extra equipment, users design their own avatars that move in the direction of other users “standing” nearby. With just a few taps of the arrow keys, users engage in socially distanced conversations.

The team is already busy working on the North Campus Grove and Law Library Reading Room on the way to making a virtual copy of the entire Ann Arbor campus.

He hopes the virtual Diag will become an enduring, “open-source” style project for many students to work on with the center’s XR team. It takes developers, designers, artists, audio engineers, storytellers, accessibility experts, and more to bring photorealistic virtual reality projects to life, Nelson said.

“It only makes sense to include people from all backgrounds to help build.”