Barry Fishman, Faculty Innovator-in-Residence

@BarryFishman

What if we could re-imagine residential undergraduate education so that it:

- Directly engages students in real-world problem solving and scholarship as the core of their learning experience;

- Makes a big university feel smaller while enhancing learning and collaboration across disciplinary boundaries, and;

- Amplifies the value of a public research university for its multiple stakeholders?

That is a lot to ask, but it is exactly what a group of faculty, staff, and students have in mind as we design the Big Idea program, introduced in an earlier post.

When designing a new educational program, it is best to start with learning goals. What will students in this program know, understand, and be able to do? Goals come first, so that when you do begin planning curriculum, activities, and other structures the goals can serve as a benchmark. Designers must continually ask, “How does this activity satisfy one or more of the learning goals leading to our desired program outcome?” In education circles, this approach is known as “backward design” (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005).

The Principal Objective of the Big Idea

The Big Idea is designed with the following top-level challenge—and how the university could respond to this challenge—as our central focus:

Society needs citizens who can identify problems in complex, ambiguous contexts and make meaningful contributions to progress towards solutions to those problems. The University of Michigan’s role as a public research university is to enable its students to gain this ability.

Let’s unpack this somewhat dense statement. A key motivation behind the Big Idea is a recognition that, while the world and its problems are increasing in complexity and ambiguity, the undergraduate educational programs we provide in higher education are too frequently designed in ways that do not support, or even undercut, students’ ability to deal with complexity and ambiguity. In part this is a response to demands from students themselves, who have grown up in a world where education systems focus on sorting and competition for access to both educational resources and jobs. From a student’s perspective, this environment is shaped by numbers; their GPA and standardized test scores.

Over the past two decades, many of the faculty involved in designing the Big Idea have observed that their students appear to be increasingly conditioned by these assessment and accountability pressures, and in response need to be given increasingly explicit instructions about not only how to complete assignments, but also in terms of what to think about. Above the level of individual courses, degree programs are structured as “checklists” of distribution credits and specialized courses that end up providing a disconnected, breadth-first learning experience. Finally, students’ extra-curricular or co-curricular experience—their life experience—rarely plays a significant role in or is counted towards their “formal” learning, because there is no obvious way to include these experiences in a student’s “score” or GPA. We argue that a different approach is necessary to achieve the goal stated above.

One could argue that the most academically “competitive” students are in some ways the most affected by this numbers-and-sorting, rule-following environment. They are usually extremely good at executing on the instructions they are given. In return, they have likely never received a “bad grade,” or done poorly on a standardized test. Their “success” is based in following the rules and executing well on everything they have been told to do. In short, they have no real experience with academic or intellectual struggle beyond the challenge of learning material for a test or prescribed assignment. The kinds of problems students face on exams or standardized tests are rarely similar to—or even good preparation for—the kinds of challenges they will face later in the workplace or the world. This is an example of assessment driving learning with negative consequences for the good of society. To address this, higher education needs to redesign assessment systems to better encourage risk-taking and exploration. (A future post will focus on assessment in the Big Idea).

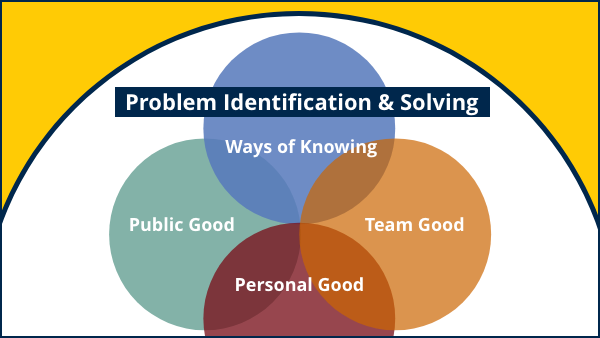

To address this disconnect between business-as-usual in higher education and the unusual demands we expect our students to face in the future, the Big Idea is built around problem identification, problem solving and preparation for ambiguity. We want graduates to have the skills and experience to make sense out of seeming disorder, in order to make progress on the really big problems facing communities, organizations, and societies.

To prepare students for our principal objective, we propose focused learning goals in four interrelated areas: Ways of Knowing, Team Good, Public Good, and Personal Good.

“We want graduates to have the skills and experience to make sense out of seeming disorder, in order to make progress on the really big problems facing communities, organizations, and societies.”

Ways of Knowing

“What do we want students in the Big Idea program to know?” That’s a good question, but we prefer to approach the answer in terms of what we want students to be able to do. We want students to develop fluency with a range of different methods for thinking and reasoning. Higher education thinkers like Charles Muscatine (2009) have critiqued the traditional ordering of academic disciplines and undergraduate distributions as inadequate, too often focused on the “objects of study” (e.g., historical knowledge) rather than the “methods of study” (e.g., historical thinking). We have adopted Muscatine’s approach, arguing that students need to develop the ability to think in and with the tools from a broad range of different thought traditions, including: Logical, empirical, statistical, computational, historical, critical (analytic, evaluative), creative and artistic. This includes fluency with both quantitative and qualitative tools for understanding, interpreting and expressing ideas and information.

We also believe that students need experience with systems thinking and complexity. This is the ability to recognize how individual components exist within larger systems, and to understand how systems interact within themselves and with other systems to produce outcomes, sometimes unexpected outcomes. Students must understand how to reason with models of systems, to explore varying and conflicting models, and recognize the difference between what is knowable and unknowable, or predictable and unpredictable.

To be effective, students need skills in both communication and information literacy. That’s why most colleges have a writing requirement. But we want to go even further. Students must be able to construct a coherent and persuasive narrative in a variety of media (written, oral, visual, and performance/physical). They need to be able to establish a meaningful connection to their audience. They need to know how to engage in productive and respectful debate. Given the complexity of today’s information environment, students need the ability to process, understand, verify, and interpret information from various sources. This includes being able to distinguish between accurate and inaccurate information, and to know how to respond to or deal with inaccurate information.

We note that the Big Idea does not put much stock in knowing “things.” This is premised on the idea that facts, formulae, and other discrete bits of knowledge are easy to look up in today’s technological climate. What is harder is to know how to use these facts and formulae; when to apply them, what they mean in context. The Big Idea thus emphasizes real-world settings and problems as sites for learning, rather than the current practice of front-loading knowledge and skills in coursework without a clear understanding of how (or when) it will be needed.

Team Good

Michigan uses the phase “leaders and best” frequently. We like this catchphrase, and want the Big Idea program to embody it. To us, “leadership” is about thinking of the team (or as U-M likes to put it, “The Team! The Team! The Team!”). Our students need experience with organizing the work of groups, including the ability to make decisions, provide supervision, and give and receive feedback. This is the heart of leadership. Sometimes leadership is about being a good team member. Being good at teamwork is about having the ability to follow instructions, and to negotiate and carry out responsibilities. Students need collaboration skills (including communication). And finally, we want learners who understand accountability, exhibit humility, and can take ownership of the results of their choices and actions.

Public Good

A public university exists for the public good. As the U-M mission statement puts it, we “…serve the people of Michigan and the world through preeminence in creating, communicating, preserving and applying knowledge, art, and academic values….” Students in the Big Idea will be engaged in community-centered research and scholarship in a variety of ways. Through this work, we expect them to develop a sense of civic purpose and engagement, including a deep understanding of community, civic, and governmental structures at all levels and the ability to participate in and contribute to the health of these structures. We want to develop a capacity for intercultural engagement, wherein students can identify cultural patterns (including their own), respectfully compare and contrast cultures, and engage in dialog to develop understanding and empathy across cultures. We expect students to develop a sense of ethics in terms of moral principles and reasoning that govern their own or a group’s behavior. And all of this requires a sense of altruism and empathy in order to identify the felt needs of individuals or groups and be able to act positively to address those needs.

Personal Good

A university education should engage students in a wide variety of projects. But it is important to remember that one of the most important projects is the student themselves. Nothing else we do matters if students, along the way to developing their skills, knowledge, and abilities in the ways described above, do not also develop as an individual. The Big Idea thus emphasizes intentionality and reflection for learners, teaching students how to formulate plans for their own learning and development in both the short- and long-term, and the ability to reflect on progress and outcomes in order to make choices about the benefits and costs of different paths forward. We expect students to challenge themselves in the Big Idea, to take on projects where the answer or outcome is unknown (even to their mentors). In such situations, we would expect that many of these attempts will not “succeed” as we traditionally understand that idea in formal education. But all attempts should result in important progress and learning. Thus we need Big Idea students to develop resilience, the ability to define and measure progress towards goals, and to recover from setbacks and failures. And we expect our students to develop self-knowledge and well-being, to monitor their own physical, mental, and spiritual health, to be self-regulating, and to be able to ask for or advocate for support or help when it is needed by themselves or others.

Recap of Learning Goals

In the Big Idea, learners will develop the ability to identify problems in complex, ambiguous contexts and make meaningful contributions to progress towards solutions to those problems.

This is accomplished by mastering learning goals in four areas:

Ways of Knowing:

- Fluency with a range of methods for thinking/reasoning

- Systems thinking and complexity

- Communication

- Information Literacy

Team Good:

- Leadership

- Teamwork

- Collaboration

- Accountability

Public Good:

- Civic purpose and engagement

- Intercultural engagement

- Ethics

- Altruism and empathy

Personal Good:

- Intentionality and reflection

- Resilience

- Self-knowledge and well-being

What’s Next?

With learning goals in hand, the work of the Big Idea group moves on to defining the core learning experiences where students will make progress towards mastering the goals. There are a number of key issues that must be addressed along the way. How do we assess learning in the Big Idea program? What kinds of students do we expect to engage with the Big Idea? How will admissions work? How will learners interact with research projects? How does the Big Idea help facilitate multi-disciplinary research projects with a community focus? Work is underway in all of these areas. Stay tuned for future posts on these and other Big Ideas!

Acknowledgements

The ideas in this post represent a group of faculty, staff, and students working on the Big Idea. This includes: Laurie Alexander, Jamie Blackwell, Norm Bishara, Bridgette Carr, Anne Curzan, Tracy de Peralta, James DeVaney, Meg Duffy, Cindy Finelli, Barry Fishman, Anita Gonzalez, Melissa Gross, Larry Gruppen, Matt Harmon, Leslie Herrenkohl, James Hilton, Paul Kirsch, Courtney Klee, Mika LaVaque-Manty, Tim McKay, Nigel Melville, David Mendez, Rachel Niemer, Ken Panko, Panos Papalambros, Andrea Quinn, Paul Robinson, Hannah Smotrich, Caren Stalburg, Verity Sturm, Stephanie Teasley, Alex Wilf, and Margaret Wooldridge.

In addition to sources cited above, the thinking behind these learning goals (and some of the language) was inspired by:

- The “Big 10 Leadership and Change Competencies” from College Unbound

- The “Essential Learning Outcomes” from the Association of American Colleges & Universities

Particular thanks to Meghan Duffy, Larry Gruppen, Panos Papalambros, Tracy de Peralta, and Caren Stalburg for their feedback and input on this post.

References

Muscatine, C. (2009). Fixing College Education: A New Curriculum for the Twenty-first Century. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press.

Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding By Design (2nd Expanded edition). Alexandria, Va: Assn. for Supervision & Curriculum Development.